Frames, Boundaries, Borderlines: NYC June 2-June 10, 2022

Reflections on a trip to NYC and the people/art that defined it, from Devin DiSanto to Nancy Graves, Suzanne Langille to James Herbert, Robert Beavers to Madonna

I’m not one to take photographs. If you see me on vacation with an iPhone in hand, it’s far more likely that I’m using the Voice Memos app over the camera. You can list any number of reasons for that: my proclivity for sound, how pressing “record” allows me to stay in the moment far more easily than taking a photo, my unintentional but lifelong commitment to never learning how to take a decent selfie. More importantly, there’s something enticing about preserving time and space through audio—such recordings feel as simultaneously banal and amorphous as memories themselves. Photos remain fixed, offering some semblance of clarity and importance; a multi-hour recording of me walking around a city doesn’t serve as a Greatest Hits collection as much as a reminder to continually appreciate all sound, all the time.

That’s especially true in New York City, which I visited from June 2nd to June 10th. There, I was constantly enchanted by the thrills of walking from one block to the next. I spent a lot of time listening to music that week—a Stravinsky opera, Steve Roach’s Ambient Church show, two Eiko Ishibashi concerts—but when removed from these music-specific contexts, I spent almost no time “listening to music,” perfectly content with the feast of ordinary sounds that always lay before me. A few months ago I was in Denver for a teacher conference and was fascinated by the city’s relative quietude—it felt like a ghost town for one of the most populated cities in the US. I often thought about the way this reality related to the people and experiences I had there. If I felt that I had only met one type of person in Denver (uh, white lol), then New York was an embarrassment of riches (literally, culturally) in comparison.

A week before my vacation, I interviewed Devin DiSanto, an artist I’d admired since his 2013 debut Tracing a Boundary. He had just released a new album called Waiting and Counting: Domestic Ritual for the Stereo Field and I was eager to talk with someone who I’ve known but only talked with intermittently. (His 2015 album with Nick Hoffman was one of the earlier pre-Substack Tone Glow reviews I’d written, and he performed a set for a Tone Glow livestream concert last year.) His procedural, work-centered, performance-art informed music always brought to mind a quote from Fluxus founder George Maciunas: “Fluxus people must obtain their ‘art’ experience from everyday experiences, eating, working, etc.” DiSanto, through his deadpan, task-oriented pieces offered a sly twist on Fluxus’s manifesto-inscribed “anti-professional” aims. If post-Fluxus musicians had always encouraged me to listen closely to sounds around me, DiSanto was doing so in a manner specific to the workplace atmosphere, all while maintaining the group’s humorous spirit.

Our conversation had stuck with me while in New York. Specifically, I was fixated on this one idea that elucidated much of his practice. He talked about walking through a forest to the space immediately outside of it, and how it’s easy to identify when that occurs just from the sounds one hears. Tracing a Boundary as a title made a lot more sense. But there was this other, related idea: that of the 1:1 match a sound can have with its meaning. He mentioned how a microwave bell indicates one’s food is ready, and that he wanted his music to be more ambiguous and expansive, allowing familiar sounds to be more than their accepted purpose and signification. As I walked from my Airbnb in Crown Heights to the train station each morning, and across Manhattan throughout most of every day, I was tickled by what was happening in my brain: I felt I was understanding various locales from their changing sonic landscapes, but I also knew it was foolish to think I really did “get” anything.

This is the dialectic at the core of my artistic interests. To write about music and film is to think more critically—to illuminate myself and others—but I also acknowledge that when an artwork has “exhausted all it can provide for me,” as I am wont to believe (subconsciously, at least), I’m approaching it all wrong. I love thinking my opinions on art are right—who doesn’t?—but I also want to believe there are other versions of “being right.” Hence my affinity for the writers panel format on Tone Glow, and my love for interviews as a way to better understand artists and their work. The latter has always been presented in a Q&A format to avoid the more explicit narrativizations in artist profiles. It’s more fun when it feels like people shooting the shit, when there isn’t a real point to any of it, much like how conversations are more fun when someone isn’t just being cordial to eventually ask a favor.

I conducted four interviews while in New York. They were with: Larry Gottheim, at the delicious Dim Sum Palace; Loren Connors & Suzanne Langille, at a Brooklyn spot where the waiter knew the former’s order (a salmon dish that wasn’t on the menu); Thomas Buckner, at his gorgeous Manhattan apartment; and Yasunao Tone, who offered slippers and tea upon my entry into his home. I enjoyed them all very much, and was pained by the thought of them being one-offs—surely there was more to be said. Knowing that I could realistically come to New York again and talk with any of these folks made me sadder than usual: Do I care about interviews and writing or do I just like talking with people and having us enjoy each other’s company? It’s the latter, of course, but that can’t exist without the former. And so I write.

I’ve often thought about keeping in touch with artists I’ve interviewed, and the taboo of writing about artists you’re close with. Personally I consider the latter kind of dumb given the small, insular nature of the music world (especially in niche scenes), but also because it assumes that I wouldn’t call a friend’s music terrible. I’m not sure there’s any real possibility for robust, thoughtful communities when neither of these things are allowed to happen. Regardless, I have not kept in touch with the overwhelming majority of artists I’ve interviewed, and the mentality I often have when conducting one is that my time with them should be pleasant and enriching, that there is some transference of my love for their art in our time together. This is the least I can offer.

This is, in some respects, how I try to approach every conversation I have, especially with people I’ve known online but are only meeting “in real life” for the first time. It feels almost imperative that I explain what I like about a person face-to-face lest I never have the opportunity to do so again. I was at a retirement party last month and cried as my coworkers gave speeches about those who were moving on. They had known these people for 30, 40 years and it was nourishing to hear stories upon stories of the way people affected them. Had these retirees known of their impact? Surely we communicate that we feel loved in nonverbal ways, but there’s something monumental about words being thoughtfully, concretely announced. After I came home to Chicago, my friend Troy—who I’ve talked with for a decade but only met for the first time last week—sent me a message: “Thanks for a bunch of fun evenings. I’m sure they will be among the best nights of my year. I already know it! Glad you’re home alright.” No one’s ever said something like that to me before. What a thing to hear—“I already know it.”

While I was planning to return home on Wednesday, June 8th, I extended my trip because Loren Connors invited me to his concert on Thursday. Suzanne said she’d put me on the guest list. I had no choice but to stay. The concert itself was phenomenal—both he and Eiko Ishibashi killed it—but at the end of the day, when I have no recollection of the music at all, there will be other parts of the night that stick out. After the show, I saw Suzanne and we hugged. We talked about Loren’s set, and I made sure to note how much I loved the way his mask, Fender Squier, and loafers all matched. I asked if she knew where he was, and without a beat she brought me to him, ensuring that we could talk despite him already being in conversation with others. There was a generosity in this action that really moved me, that no matter what, she was making sure that we’d talk.

It reminded me of my conversation with her from days earlier. I asked about her work as a lawyer, where she serves the city in matters related to public health and environmental justice. In a decade-old interview she mentioned fighting against people like Michael Bloomberg. “Do you get intimidated?” I asked. She told me that if her job were easy, she’d get other people to do it. She does her job because it’s tough. If not her, then who? This is the sort of life I want, one where boldness and compassion underline everything. Who cares about anything else.

When Suzanne brought me to Loren, I instantly recalled a different, similar thing that happened to me: A couple weeks after talking with Annea Lockwood on the phone, I saw her in Chicago as part of the city’s annual Frequency Festival. When Annea noticed I was in the room, she took my hand, brought me to a different space in the venue, and sat me down in a chair beside her so we could devote time just for us. I brought my copy of Dump / State Of The Union Message / Tiger Balm for her to sign, and while I don’t remember what she wrote, I’ll never forget the thoughtfulness of that moment, of her stepping aside from everyone else to talk with me.

At the heart of both these events is that these people made me feel special. While reflecting on all this, I realized that a part of why I enjoy and am perhaps good at doing interviews is that in some sense I’m making artists feel special. This is distinct from ego-stroking and fanboying, though I suppose the only difference is the degree of intentionality and respect. I have a large disdain for celebrity culture and have never been starstruck—reading Studs Terkel’s Working does that to you—but it was still surprising when, after the Loren Connors & Eiko Ishibashi show, I saw Jim O’Rourke outside and he told me, “Thank you for everything.”

There was a slew of art I consumed throughout my stay in New York, and the stuff that struck me most legitimately shocked me. On Monday and Tuesday I spent a lot of time at the legendary Film-Makers Coop devouring avant-garde films. The Paul Sharits films were especially thrilling, with Apparent Motion (1975) being a real-deal “I can’t believe my eyes” moment. The film is constructed from six superimposed layers of film grain that have been enlarged via optical printers. It’s a kaleidoscopic formal exercise that bewildered me—I swore I saw text being formed from specific colors, and my friend Mark, who I saw the film with, believed the same. More confusing was that beyond the individual dots, it felt like the entire frame was actually moving. I love when I have to second guess my senses; I’ve been seeing my whole life—you’re telling me my eyes are more futile than I think? Incredible.

There was also James Cagle’s films. His Waterwork (1973) is a structuralist masterpiece, and consists of nothing more than a single zoom on rushing water. It’s simpler than Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) but better for it, as the film becomes increasingly astounding (read: preposterous) as it zooms in on these waves. Matrix (1973) was equally invigorating, as it’s a flicker film with a sense of humor, highlighting the strangeness of his wife’s face as shadows and the inversion of colors lead to her looking alien, demonic even. I also watched four Brakhage films, the best of which was Jesus Trilogy and Coda (2001). The beginning of its second part was especially moving, as different superimpositions of hand-painted film had contrasting rhythms, performing their own intricate pas de deux—the slow dissolves were unexpectedly seductive.

These aforementioned films are the sort that excite me because they point towards the boundlessness of the medium itself, but the films I really can’t stop thinking about are those that subverted expectations. Ed Emshwiller Dance Chromatic (1959) has this old-school hokeyness to it that could easily cause cynics to roll their eyes, but I sat mouth agape as it brought together choreography, color, and texture in the most playful of manners. It’s this experimentation-as-play aspect that was crucial, and it’s what drew me to Robert Beavers’s Still Light (1973). Much to my delight, I saw that film and 12 others at the New York Public Library, and was given the freedom to thread the projector myself and move at my own pace. Still Light was one I watched twice because of how inviting it was. It’s a classic Beavers film in its directional swipes, evocative nondiegetic sound, seductive re/unfocusing, and simple methods of reframing images. The crux to it and his best films, such as From the Notebook of… (1971), is that it’s so obviously curiosity-driven, causing secondhand excitement for the playful experiments he engages in. That childlike dedication and joy is felt in its candied rainbow colors, and he helps you recognize that experimental filmmaking is hands-on, exploratory, audacious, and fun.

The most indelible film of the 24 I saw was James Herbert’s Apalachee (1974). I didn’t love the whole thing, but Herbert has always been a director I’ve been conflicted about. His Porch Glider (1970) is all cozy eroticism, with shots of domestic life and naked bodies bearing the tenderness of honeymoon-phase love. Something like Carnival (1983), though, is absolutely horrid. While an interesting curio for featuring the entire recorded output of the obscure Athens, Georgia-based band Limbo District, its editing is so choppy that it instills in me a deep hatred for its existence—it feels like a slideshow more than anything filmic. Apalachee somehow merges both of these film’s sensibilities and comes out unscathed. One could remark that it’s some hippie-dippy shit, being little more than white, conventionally attractive heterosexuals making love in a forest and the ocean. It definitely is that, but its jerky start-and-stop rhythm grants it an alluring disorientation. Herbert finds a balance between the memory-capturing delicacy of still photos and the evocative movement of the filmic medium and the result is like your heart’s fluttering. Brief pauses of water lapping onto genitalia, or a leg wrapping around another… this is the “holy shit, holy shit” in-the-moment/outside-of-time feel of impassioned love. It’s like the melding of body and nature in Amy Greenfield’s Tides (1982) but with lovers.

If there was any artist who made me think deeply about humanity’s relationship with the world, it was Nancy Graves. Throughout her life, the sculptor, painter, and filmmaker refused to be pinned down, but there was this irresistible element of movement in her works. I visited the Nancy Graves Foundation on Wednesday and saw some of her sculptures in the facility, impressed by the way their curvatures and materiality forced one to circle them and experience how they’d feel different from varying vantage points. I was initially drawn to her works via her films, of which Izy Boukir (1970) and Aves: Magnificent Frigate Bird, Great Flamingo (1973) are among the best animal-focused films I’ve seen. The former begins with the following quote from author and naturalist Henry Beston, from his book The Outermost House: A Year of Life On The Great Beach of Cape Cod (1928):

We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate for having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein do we err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.

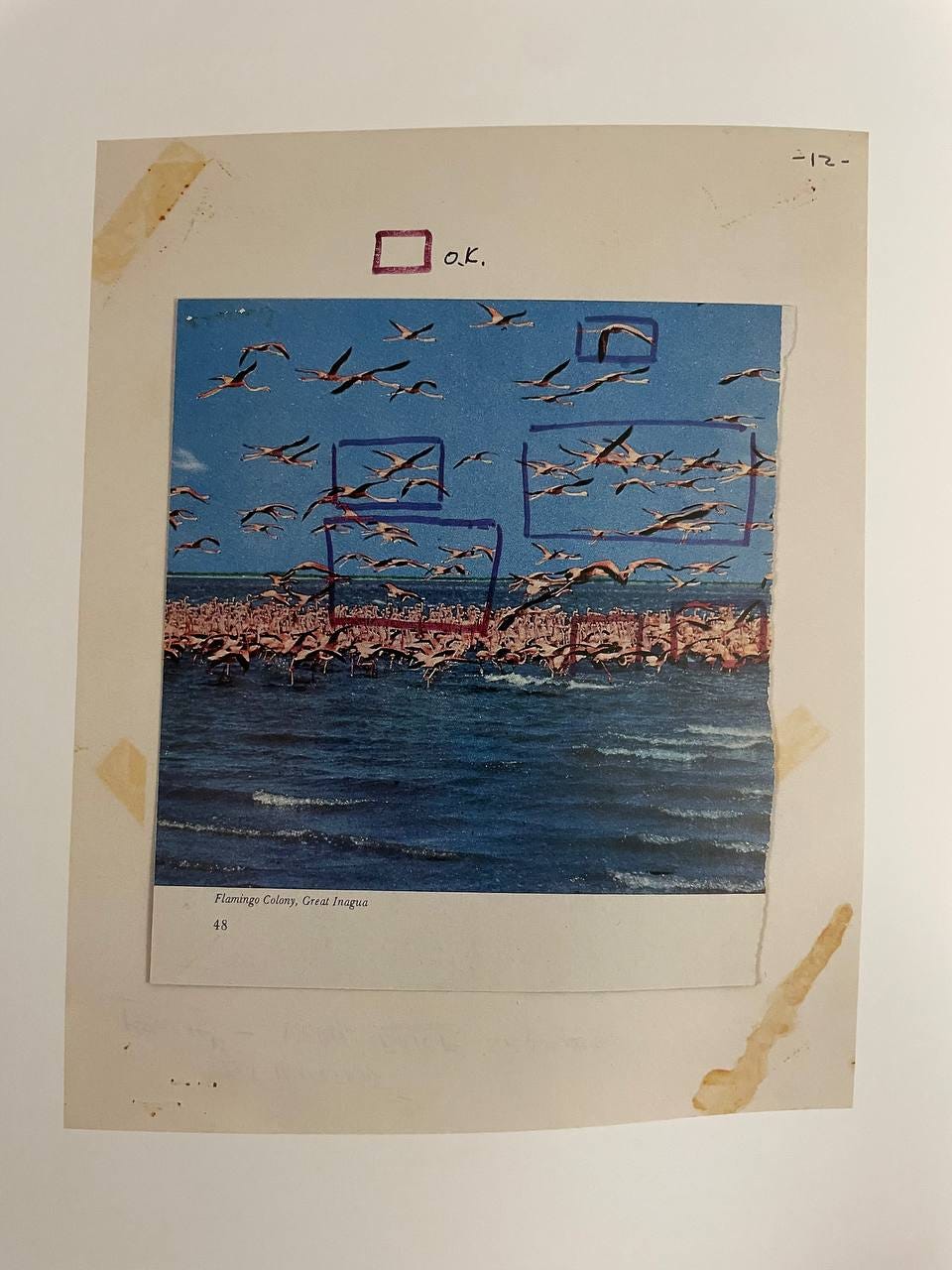

It’s a really beautiful thing to consider oneself as a mere interconnected blip in this web of life, and it’s really meaningful to me that Graves was able to make films that communicated that idea. I spent most of my time at the foundation looking through the archives. With gloves on, I parsed her preparatory notes for Aves and marveled at what I saw. There were numerous clippings from nature magazines and the like, with pink boxes indicating how she’d specifically want these animals to be framed. Alongside these were specific rules: “No Comedy,” “No Anthropomorphism,” and “No Parents + Young Sequences” were some of the most interesting. What was clear was that, compared to nature documentaries that try to make animals relatable, Graves sought to maintain these creatures’ elusive mystique, ensuring that we weren’t “bringing them to our level.” Why try to relate to animals in a way that makes them reducible? Why not make them relatable for their slipperiness, their infinitude?

Infinitude is, consequently, the word at the heart of my entire trip to NY, but it’s also central to my life at large. I conduct interviews because I feel I can learn something from everyone I talk with, and sometimes that means learning something about myself. One moment that stands out in my conversation with HTRK was Jonnine Standish stating, “It’s how I try to live my own life as well—surprising people’s expectations of you.” I don’t think I do that very often, but I do like the idea of surprising myself, of realizing that I can be something far more than I ever thought possible. This is why it’s so nice to talk with others, as it gives implicit permission to live life in courageous ways. It’s also why I spend so much time thinking about art—if I’m understanding music and film in new ways, then there’s a chance to think about life differently, too, and my life specifically. It’s addictive to dream big.

Though I spent roughly 95% of my time in New York not listening to music while walking, the other 5% was dedicated to one song I had on repeat: Madonna’s “Borderline.” It’s her best single, and the seven-minute version is my go-to. The writing I’ve seen on it feels incomplete, though. On the surface, yes, this is a song about Madonna putting in more work than her lover, and being devastated by that truth. But it’s not dramatic or dynamic enough to ever feel like she’s actually pushed beyond the song’s confines and comforts. When you listen to the song, and especially when you sing it, “Borderline” feels cheerful. It has the semblance of looking back, with an almost unthinkable nostalgia, on these terrible times in your life. Somehow, time makes things forgivable. And it’s not that it wasn’t horrible, and it’s not that you’d ever live through it again, but more so that this is your life—you’ve lived it and you’re still here.

There’s this one part of “Borderline” that’s been lodged in my brain. It’s when Madonna wistfully sings, “Keep pushin’ me, keep pushin’ me, keep pushing my love.” Is it a sly taunt? A masochistic demand? The more I listened, the more I considered it to be a recognition of what sometimes happens in life: you love and love and love, and nothing comes of it. But that loving can feel good regardless because it’s the emotion that demands the most of you. It’s the emotion that actually demands you, that demands you.

I embarked on my trip to New York because of a group of friends I’ve known for a decade—we knew each other via the internet, initially via the Last.fm group “Lair of Despair.” Some of us have met individually throughout the years, but this was the first instance that a lot of us decided to travel and meet up. It was a lovely, memorable time, and I’ve been telling them that I really do think that, in some small way, it changed my life. I’m also recognizing more fully that music as something social is something relatively new to me, even after all these years.

When I first learned about Devin DiSanto’s music, I was still in college and wasn’t on any social media. I never got a MySpace, didn’t have Facebook, was averse to Snapchat, and wouldn’t touch Twitter or Instagram for five more years. I chalk that up to deep insecurity more than anything else, just this deep fear of “being perceived.” On that Thursday after the Loren Connors and Eiko Ishibashi show, I kept cycling between different groups of people. My friend Troy remarked at one point, “there was like a line of people waiting to talk with you.” It was a surreal experience. I can’t remember the last time I conversed with so many people who wanted to talk with me, and I certainly never talked with so many people as a result of anything I did in the arts. My life as a high school science teacher has kept me far removed from that, and I’ve enjoyed that. But I’m learning to accept that people care about the things I’ve done, and to receive the love that comes as a result. It’s this idea of frames and boundaries and borderlines, that they can always shift, and that we can partake in that. I don’t think I ever want to know who I’m gonna be years from now, because I don’t want to settle for whatever my brain can muster up. It’s art and others who will shape me into someone I’ll never expect, into something that will legitimately surprise me. If there’s one thing I ask of everyone and everything, it’s this: keep pushing my love.

When I landed in Chicago, my father picked me up from O’Hare and told me a story as we drove down I-90. It was about his father, and how he’d occasionally say that, despite all he’d gone through, he wouldn’t change his life for anyone else’s. When my father got older, he realized he could say the same. “You probably feel the same way too, right?” I nodded in agreement. Merely by habit, I recorded that conversation on my phone. A photograph wouldn’t have been the same.

A Gift for You

I recorded Loren Connors & Eiko Ishibashi’s live sets at Artists Space on June 9th, 2022. These recordings were done with my Zoom H2n handheld recorder from where I was sitting, which was right in front of the stage. The recordings are not great (that’s an understatement lol), as you can hear my moving my body (I always move my body whenever I hear music, regardless of the genre), and there’s clipping that occurs too when the music gets too loud. Still, I’m sure someone will wanna hear these, so here we are:

Loren Connors live at Artists Space on June 9th, 2022

Eiko Ishibashi live at Artists Space on June 9th, 2022

Record Keeping

An incomplete list of every person I met in NY, listed chronologically by the first day I met them, along with a truncated itinerary:

Thursday:

Mark C.

Fabian G.

Jon S.

James B.

Friday (Interview, Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress):

Larry G.

Emily W.

Julia V.

Troy S.

Leena M.

Saturday (Scent Bar, Paradise of Replica, Steve Roach Ambient Church show):

Bingham B.

Nick Z.

Sunday (Interview, The Met Cloisters, dinner at Gage & Tollner, Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future):

Loren C.

Suzanne L.

Monday (Interview, Film-Makers Coop):

Thomas B.

M.M. S.

Ian A.

Cath K.

Tuesday (Film-Makers Coop, Interview, Dinner with Tone Glow folks):

Yasunao T.

Eli S.

Chloe L.

Evan W.

Vanessa A.

Wednesday (NYPL, Michael J. Schumacher & Eiko Ishibashi at Artists Space):

Christina H.

Johnny G.

Crystal L.

Adrian R.

Max M.

Daniel D.

Jack C.

Tyler M.

Steve S.

Eiko I.

Jim O.

Thursday (Poster House, Ergot Records, Loren Connors & Eiko Ishibashi at Artists Space):

Malkah M.

Cody D.

Jacob G.

Jadelain

Dan G.

Thanks for this beautiful and wise reflection about the relationships between art and friendship and life. You're an inspiration, Joshua!